An Expanse of Stillness

In Conversation with Katherine Colborn

February 22 , 2022

By Side x Side Contemporary

By Side x Side Contemporary

Katherine Colborn is an artist living and working in Cincinnati, Ohio. She received her BA in Studio Art and English from Xavier University and her MFA in Studio Art with a focus on Drawing and Painting at the University of North Carolina Greensboro. Her work engages with themes of sanctuary and threshold, exploring the place of painting in a culture that values speed and production while saturated with an abundance of imagery.

In 2015, she completed an artist residency at the Burren College of Art in Ballyvaughan, Ireland. Her work has been published internationally in ArtMaze Mag and she has exhibited her work around the United States; recent exhibitions include solo shows at ROY G BIV Gallery, Kansas City Artist Coalition, and Greensboro Project Space, as well as in group shows with the Bolivar Gallery at the University of Kentucky, Ejecta Projects, and the Weatherspoon Art Museum, and in nationally juried exhibitions at Site: Brooklyn in New York City, Manifest Gallery in Cincinnati and Wichita Center for the Arts in Kansas. She currently teaches drawing, painting and foundations at Northern Kentucky University and is preparing for an upcoming residency at Vermont Studio Center.

In 2015, she completed an artist residency at the Burren College of Art in Ballyvaughan, Ireland. Her work has been published internationally in ArtMaze Mag and she has exhibited her work around the United States; recent exhibitions include solo shows at ROY G BIV Gallery, Kansas City Artist Coalition, and Greensboro Project Space, as well as in group shows with the Bolivar Gallery at the University of Kentucky, Ejecta Projects, and the Weatherspoon Art Museum, and in nationally juried exhibitions at Site: Brooklyn in New York City, Manifest Gallery in Cincinnati and Wichita Center for the Arts in Kansas. She currently teaches drawing, painting and foundations at Northern Kentucky University and is preparing for an upcoming residency at Vermont Studio Center.

Thank you for taking the time to chat with us. Can you tell us a bit about your work and ideas that you pursue in your practice?

Thank you for the opportunity! For the last few years, I’ve been focusing on the notions of sanctuary and threshold. There are both scholarly and personal motivations for this. I’ve studied philosophy, literature and theology, and I’ve been fascinated with the idea of apophatic theology—also called negative theology. It’s the active study of that which we cannot fully understand or even name. How does one begin to explore something that can’t really be cognized? I think it’s amazing that there is an entire field of study dedicated to idea of something that—by its very nature—we acknowledge we won’t ever be able to completely understand. It’s precarious and mystical. It’s a never-ending mystery. I can’t say that I make work because of these ideas, but I think these ideas are giving language to many questions I am asking in my work. They weave in and out of the making.

You would think that these kinds of ideas would lend themselves well to fully abstract work (which might seem more open, or provide for a more accessible kind of intimacy), something Reinhardt did so extraordinarily well. This is where my personal motivations direct my work. There are representations in my paintings that often allude to spaces and moments from my own childhood and my mother’s childhood. My grandparents’ home (and other domestic spaces like it) have become a metaphor for my complicated relationship with liminal spaces—those in-between places and moments that often hold space for the unknown in a way unlike any other. Domestic spaces are places of rest. But they also can serve as records of time, which reminds us that they, like everything they hold, are not permanent fixtures. I make these paintings because painting—the object and the act—teaches me how to rest in a constantly changing world. It offers up visual and imagined space to better grapple with that change. It presents a case for stillness when I am unfocused, and it offers an expanse when I feel trapped.

Tell us more about this conceptual relationship that your work is making with the medium of painting itself.

Paint is such a magical thing. In these last few years, my materials are more closely embodying my ideas. Oil paint, as many artists know, is a slow-drying paint (compared to so many other types of paint). I like the idea of making work that cannot exist without a certain chronology; I like the idea of making work that requires time—it demands it. No matter how irritated or impatient I feel, it doesn’t change time. My paintings are made using thin coats of material and very few (if any) solvents or additional mediums. Often, they require several layers which need individual drying time. There is not really a speedy alternative, or way to cheat the system of time or weather (which admittedly has an impact on drying time…humidity makes a difference), just like there is no way to slow down or speed up your life. It’s a good practice in patience and presence.

I also, like so many painters, have a great affinity for the tactile nature of the material and must acknowledge the historical conversation I enter every time I pick up a brush. I have used a traditional gesso mixture for many of the panels I paint on, and preparing those panels is a ritualistic activity that makes me feel connected to Orthodox iconography. Traditional icons are meant to serve as entryways, not as surfaces or objects. They return your gaze and they open up a connection with the divine. This is not what my own paintings are designed to do, but I welcome iconography’s influence when I am working.

There is a sense of quietness in your work. This quietness is also present in your minimal color pallet. How does this sense of place and feeling translate in your work?

Yes. I’m actually little surprised by how minimal my work has become in the last few years. It wasn’t something that happened consciously. However, I spent a lot of time in graduate school trying to shed the idea that ‘more’ equates to ‘better’ and learning that true mastery often involves a sensitivity to what is truly needed in a work, and what is not. The more time I spent reflecting on what I really wanted from my own art practice—that is, when I figured out the questions I was asking, the more it made sense to reduce my use of color and limit my range of contrast. I wanted to create a space that was quiet enough to make room for the impossible in-between space—or the ineffable unknown—that I was (and am) chasing. So softer colors and compressed contrast ranges made sense. My aesthetic choices have to follow where my questions lead.

There seems to be both emptiness and presence—as if someone just left the frame—in your subject matter. You refer to a sense of transition or liminality that the space of home represents. You also talk about the idea of rest as a way to navigate upheaval. Do you think that your approach to these topics is counter-cultural?

Yes. That’s an astute observation. I don’t know if my approach to these ideas is counter-cultural, as it depends on the culture we’re talking about. I think these ideas are leaning towards being counter-capitalist. I also don’t think my interests or wants are unique—I think there are many artists, many people in general, who struggle with the whiplash that accompanies the experience of, as Arden Reed described it, being left “speeding along the Autobahn of modernity, searching for rest stops and finding them shuttered.”

I think there are many people who have these questions or might want to explore these ideas—but we live in a system that consistently rejects the value of rest and is designed to profit off of our anxiety and distraction, so it may feel counter-cultural in that sense. There are so many incredible activists and writers and artists who are reminding us of this. I don’t feel that I’m alone. If anything, I feel that my work is one voice among many.

Are you interested in interactive or performative aspects in your work? Your installations seem to provide a kind of meditative viewing space. Does the relationship of size and format play into this for you?

I would say I am certainly interested in the contingent event that occurs whenever a viewer enters a space also occupied by artwork. In the last five years, I’ve really come to recognize the importance of scale in a new way. I want viewers to relate paintings to other aspects of their lived experience—in some cases, that means the windows on a bus or an airplane, like in Sabbath Travel. In some cases, that may be opening a book, or a mirroring a literal triptych altar piece that could exist in museum or local church, like in Hiding Place. In some cases, it’s the simple recognition of a physical arch or threshold that fits the size of the viewer’s own body, like in Regrounding. I want my work to invite the viewer recognize these quiet and mysterious spaces as places for their mind to find peace with strangeness or unknown, but I also want those viewers to be able to connect that idea with their own activity—flying in an airplane, opening a book, or simply moving their own body in space.

In some ways, your work feels very poetic. Are you inspired by any poetry or music, or is writing ever a part of your artistic process? What are some of your inspirations and processes in your work?

Oh gosh—of course! My mother is an English teacher, and I (luckily) grew up in a family that really valued reading. There are so many writers and poets whom I credit for the development of my humanity, let alone my artistic work. I do have a few sources that I connect specifically to my work over the last few years. As far as poetry, I have been inspired by Rilke’s Book of Hours, and Abraham Joshua Heschel’s The Ineffable Name of God: Man. I have also been reading the poems and lectures of John O’Donohue a lot lately. Some other really excellent books that I would recommend are Jenny O’Dell’s How to Do Nothing, Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space, and Arden Reed’s Slow Art—all had a hand in the conceptual development around this recent body of work. Susan Stewart’s On Longing really changed the way I thought about scale and narrative in my work. I’ve loved a lot of the interviews I’ve read with Vija Celmins. I also think often about Lawrence Weschler’s essay Vermeer in Bosnia, which explores the near-magic in Vermeer’s ability to suggest little windows of domestic peace during a chaotic time—particularly during a plague, which seems fitting for the contemporary moment.

As far as processes go, I do try to ritualize my time in the studio. I often light a candle, listen to audiobooks or music, and always have a cup of coffee nearby. Sometimes I go through my sketchbook or old photos for direction. I find that writing is especially helpful—my sketchbook is full of notes. However, I’ve learned the hard way that I can only make good work when I’m not particularly analytical. To quote the rules that the artist Corita Kent once wrote for her students, “Don’t try to create and analyze at the same time. They’re different processes.” I usually spend time making work one day, and come back the next day to write about it, assess it, and determine whether or not things are working.

What’s next for you? Do you have any art resources to share with our readers?

Well, I was accepted into the residency program at Vermont Studio Center back in 2020, but that has been repeatedly delayed due to COVID-19. So while I hope to get there sometime soon, the exact timing is still up in the air. In the meantime, I will continue teaching until this summer, during which I am hoping to spend a lot of much-needed time in my studio. I’m also hoping to travel to New York to do some museum and gallery-hopping, and then spend time hiking upstate in the Adirondacks.

As far as resources go, there are so many favorites I could share. I recommend following the online platforms of the Nap Ministry and the Coastal Post. I’d also recommend anything written by John Yau in Hyperallergic (or otherwise) and Krista Tippet’s podcast On Being.

* For more information on Katherine Colborn’s work, please visit her website and Instagram.

Interview by:

Side x Side Contemporary

Mana Mehrabian & Krista Brand

Image list:

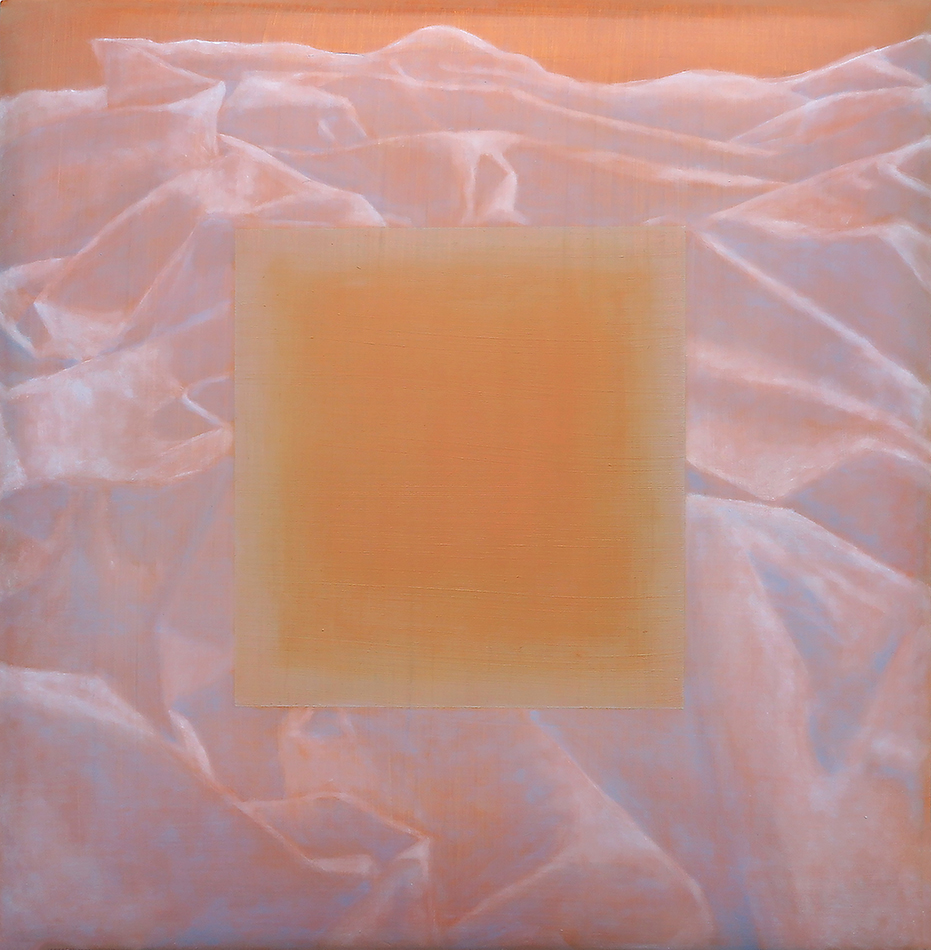

Image 1: Katherine Colborn, Regrounding, 60 x 48 in., Oil on canvas, 2021

Image 2: Katherine Colborn, Hiding Place, 12 x 18 (open) / 9 (closed) x 1 in., Oil on shaped panels and metal hinges, 2021

Image 3: Katherine Colborn, A Softer Origin Landscape, Oil on shaped gessoed panel, 12 x 12 in., 2020

Image 4: Katherine Colborn, Holding Space, Oil on shellacked panel, 12 x 9 in., 2019

Image 5: Katherine Colborn, Sabbath Travel, 60 x 216 x 11.5 in., Oil on shaped, gessoed panel, and red oak ply benches

Image 6(Left): Katherine Colborn, Dual Consecration, 12 x 9 in., Oil on gessoed panel, 2019

Image 7(Right): Katherine Colbor, So Short a Distance, 12 x 9 in., Oil on gessoed panel, 2019

Image 8: Katherine Colborn, Washing, 10 x 10 in., Oil and graphite on gessoed panel, 2019

Image 1: Katherine Colborn, Regrounding, 60 x 48 in., Oil on canvas, 2021

Image 2: Katherine Colborn, Hiding Place, 12 x 18 (open) / 9 (closed) x 1 in., Oil on shaped panels and metal hinges, 2021

Image 3: Katherine Colborn, A Softer Origin Landscape, Oil on shaped gessoed panel, 12 x 12 in., 2020

Image 4: Katherine Colborn, Holding Space, Oil on shellacked panel, 12 x 9 in., 2019

Image 5: Katherine Colborn, Sabbath Travel, 60 x 216 x 11.5 in., Oil on shaped, gessoed panel, and red oak ply benches

Image 6(Left): Katherine Colborn, Dual Consecration, 12 x 9 in., Oil on gessoed panel, 2019

Image 7(Right): Katherine Colbor, So Short a Distance, 12 x 9 in., Oil on gessoed panel, 2019

Image 8: Katherine Colborn, Washing, 10 x 10 in., Oil and graphite on gessoed panel, 2019

© All Images courtesy of the artist